Sovereignty—A Primer on How to Lose Your Country

“Banking was conceived in iniquity and was born in sin. Bankers own the earth; take it away from them but leave them with the power to create credit; and, with a flick of a pen, they will create enough money to buy it back again…. If you want to be slaves of bankers and pay the cost of your own slavery, then let the bankers control money and control credit.”

~ Sir Josiah Stamp (Director, Bank of England, 1928-1941)

“The often-repeated quote attributed to Stamp may well be apocryphal, but its inherent violence is all too real—and we are rapidly approaching its logical conclusion.”

~ John Titus

By John Titus

I. Introduction

The story of sovereignty in the U.S. today is that of the American Revolution in reverse.

The American Revolution represented the ouster of a tyrannical sovereign unbound by any legal constraint whatsoever, an ouster that was followed a few years later by the installation of a government where law was supreme over all—over even the top government officials themselves. The literal revolution that occurred in the colonies was that of the Rule of Law prevailing over the rule of man, which had proved itself far too abusive for far too long for there to be any other way of going about things.

That great, revolutionary order of things is today being reversed, as a self-anointed “elite”—some of whom are government officials, many of whom are not—disregards the law altogether and attempts to impose an endless array of arbitrary and capricious “rules” that seem to change with the wind. “Whatever we say, goes,” seems to be the mantra of these faceless technocrats, followed quickly by, “do as we say, not as we do.”

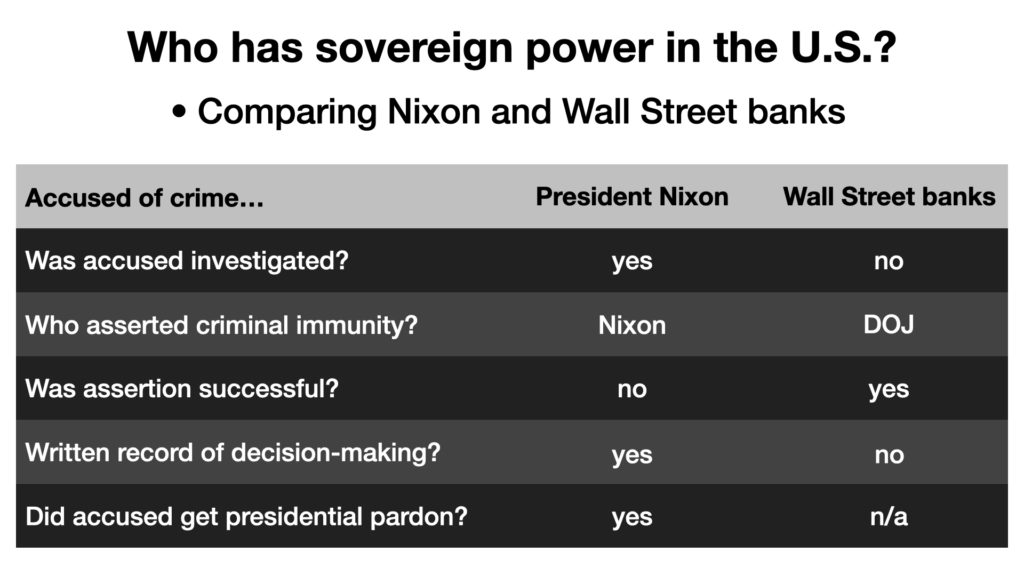

That reversal reached an inflection point—possibly irreversible, it is up to us—with the Troubled Assets Relief Program (TARP) bailout of 2008, when the will of 99% of people was ignored so that banks could be bailed out (and could pay bonuses, putatively in order to remain “competitive”). As ugly and dishonest as that episode was, the real trouble did not begin until President Obama’s first term began in January 2009. As the crisis subsided and the time for reckoning came, it became increasingly clear that there would be no reckoning to speak of, that neither Wall Street banks nor any of their executives would ever be prosecuted. As I will set forth below, that outcome could only have been, and indeed was in fact, the result of a coup d’état: the rule of law was jettisoned, officially, to make way for the new sovereign power in the U.S., namely, too-big-to-fail banks. And with that, the American Revolution was pretty much reversed.

But just as with the decade-long period in between the American Revolution (when a new sovereign was installed in the form of the Rule of Law) and the signing of the U.S. constitution (spelling out how the new order of things was to go under the new sovereign), so, too, has there been a stretch of time now when the new order of things is being sorted out; we are still in that period, though it is getting late.

Because we are watching the usurpation of sovereign power, more or less in real time, this essay examines the historical record in order to ascertain exactly which sovereign powers have been filched so as to enable the great reversal, or “reset,” that is taking place. It is hoped that this study in raw sovereign power might be useful in preventing the untrammeled exercise of power by people who are, at their very best, up to no good—before it is too late.

II. Sovereignty: Extrinsic, Intrinsic, and Personal

A. Introduction

The word “sovereignty” is likely to invoke one of three different concepts, even if we do not consciously appreciate the distinctions among them.

First, there is extrinsic sovereignty. Extrinsic sovereignty concerns the relationship between two or more nation-states and the proper boundaries between nation-states, both territorial and legal.

Russia—or at least the mainstream media’s coverage of Russia—illustrates both the territorial and legal boundaries of extrinsic sovereignty. Russia’s invasion of the Ukraine presents an example of territorial sovereignty, in particular the right of the Ukraine to exclusive possession and security within her border. Contrast that with media accounts of Russia’s alleged (or imagined) interference in the 2016 U.S. election, which presents an example of a breach of legal boundaries, in particular the sovereign right of the U.S. to conduct elections. In both cases, extrinsic sovereignty concerns a country’s relationship or conflict with one or more other countries.

On this score, the transformation of the American colonies into a full-fledged nation was massively influenced by universally recognized notions of extrinsic sovereignty. As British colonies, “America” was off-limits to potential allies such as France and Spain due to notions of extrinsic sovereignty that remain very much in place even today.

The second sense of what sovereignty means is intrinsic sovereignty. Intrinsic sovereignty concerns not only the relationship between the sovereign power of a country and her inhabitants, but also how sovereign powers themselves are delegated and used within a government in which sovereign power is less than absolute.

In medieval times, sovereigns wielded more or less unlimited power over inhabitants within their fiefdoms, with little input—certainly without elections—from those inhabitants. Those two features of the medieval age—no elections and absolute power of sovereigns over “their” subjects—are obviously closely related.

During the Enlightenment, political philosophers like Thomas Hobbes and John Locke began chipping away at the notion of absolute power by advancing models of sovereignty that imposed limits on the sovereign himself. Notions like the consent of the governed and the Rule of Law became widespread and took on huge significance among educated people, who didn’t take kindly to what they saw as outright abuses of sovereign power.

Indeed, during this period the very notion of who should wield sovereign power was altered forever. Again, the American colonies supply an example: the colonists “threw off” King George III (a man) with the Declaration of Independence in 1776, and eleven years later the U.S. Constitution formally installed “We the People” as the official sovereign of the nation, which was bound under a system of laws to which the people freely consented.

Finally the word “sovereignty” may invoke the notion of personal sovereignty. History again acts as guide. The most salient example of the lack of personal sovereignty is slavery. Slaves had no rights of self-determination. Legally they were chattels, and indeed for purposes of taxation, slaves were treated by the U.S. as three-fifths of a citizen.

Importantly, the institution of slavery didn’t end with the ratification of the U.S. Constitution but rather extended for almost another century. Crucial in bringing slavery to its end was the Rule of Law—the notion that if no one was beneath the law’s protection, then slavery had no place. The Rule of Law was inextricably bound up in both the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, where the principle of the Rule of Law is much closer to the surface. “Who are you,” the document asks rhetorically of the king, “to abuse us by feigning superiority to the law itself in your abuse of us?”

Thus, the issue of personal sovereignty, to the extent it has begun to percolate to the surface with the relentless drive for mandatory vaccinations, hints at fundamental abuses of power that overlap to a great degree with the intrinsic sovereignty of a nation. As such, individual sovereignty will not be treated separately below; the issue is raised here as a red flag concerning the times in which we live.

B. Extrinsic Sovereignty

The notion of extrinsic sovereignty involves the relationship between two or more nation-states. It tends to make the news when those relations go awry. Recent events involving territorial sovereignty in the Ukraine supply ready examples.

From the point of view of NATO, Russia’s invasion of the Ukraine is a straightforward breach of the latter’s physical borders. As such, it violates internationally recognized norms of “sovereignty,” in particular about the sanctity of a nation’s borders. From the point of view of Russia, NATO’s activities in the Ukraine, including the installation of some two dozen biological “research” (read: warfare) labs, posed an existential threat to Russia that required the removal of NATO-installed forces within that country’s borders.

Extrinsic sovereignty is not limited to territory, however.

The aftermath of the U.S. election in 2016—at least the story of that election as imagined by members of the media once the surprise outcome became official and defied nearly all their predictions—provides an example of extrinsic sovereignty involving the breach not of territorial but of legal boundaries. The media endlessly repeated allegations that Russia had interfered in the election in a way that helped Donald Trump and hurt Hillary Clinton; indeed, the claim was made that but for Russia’s alleged interference, Hillary Clinton would have won the election and become the first-ever female president.

These latter allegations about Russian election interference concern breaches of law, not of physical territory. Russia was (and is to this day) said to have improperly funneled money into the political coffers of Donald Trump, as well as to have improperly interfered with U.S. affairs by posting pro-Trump and anti-Hillary messages on (heaven forfend) FaceBook and other social media sites. Neither the alleged supply of money nor the alleged social media interference involved any territorial invasion; rather, these claims go to legally improper meddling with the sovereign right of the U.S. to conduct elections.

In both cases of extrinsic sovereignty, had any of the allegations ever been backed up with any forensic or physical evidence, it would indeed be true that Russia had violated U.S. sovereignty as alleged. Our point here is merely that the affair is an example of sovereignty. But where do our notions of extrinsic sovereignty come from?

Definition and Scope of Extrinsic Sovereignty

Modern notions of extrinsic sovereignty date back to and arise from the Peace Treaty of Westphalia. The two principal notions of Westphalian sovereignty are now so widely accepted that they are completely non-controversial: (1) each country is absolutely sovereign (that is, supreme) within her territorial boundaries, irrespective of the form the sovereign of the country takes; and (2) other countries should not meddle in or interfere with a country’s internal or domestic affairs.

The part of the definition of sovereignty from Black’s Law Dictionary emphasized below captures the essence of Westphalian sovereignty:

The possession of sovereign power; supreme political authority; paramount control of the constitution and frame of government and its administration; the self-sufficient source of political power, from which all specific political powers are derived; the international independence of a state, combined with the right and power of regulating its internal affairs without foreign dictation; also a political society, or state, which is sovereign and independent [emphasis added].1

Notice what is absent from the scope of Westphalian sovereignty: freedom from interference in its internal affairs by non-state entities like global corporations or organizations.

The omission can be dealt with, at least in part, by notions of intrinsic sovereignty. In particular the intrinsic sovereign power of a country to punish lawbreakers and criminals could presumably act as a check on non-state global intermeddlers—but only if those actors are within the borders of the nation so victimized (or otherwise legally reachable by, say, treaty).

The materiality of this lack of coverage by Westphalian sovereignty will become apparent in the next section.

Role of Extrinsic Sovereignty in American Revolution

Antagonism between the American colonies and the Crown festered for decades before really ramping up throughout the 1760s and coming to a boil during the 1770s. Yet as much as a growing percentage of colonists wanted to rebel against the Crown or even break free, their status as mere Colonies of Great Britain hobbled any such efforts due to the international acceptance of Westphalian sovereignty principles. Other nations, in particular France and Spain, simply were not willing to meddle with what boiled down to a purely domestic affair of the Crown: regardless of whether the colonial dispute was labeled a rebellion or a civil war, either way it was purely internal to Great Britain.

There was simply no way for the colonists to get the reforms they wanted from the Crown—at least not as colonists. They had tried to get what they wanted by getting the Crown to grant their many petitions. This much is clear from the long recitation of grievances in the Declaration of Independence; the grievances appear in the Declaration precisely because every single one of the corresponding petitions had been denied.

And there was no way for the colonists to get what they wanted by force since any rebellion would be crushed. As a group, the colonists were a collection of farmers up against the most powerful empire in the world. At best, the colonists were a weak militia, with no navy and precious little gunpowder not already dedicated to feeding themselves.

What the colonists needed was allies like Spain and France. But as a collection of British colonies America lacked the standing needed to enter into treaties that could shore up the colonies’ critical shortcomings as a power that could take on the Crown militarily. And again, Spain and France were precluded by the principles of Westphalian sovereignty from meddling in Great Britain’s affairs.

However, what the colonists lacked in arms, supplies, and money, they made up for in political (and legal) innovation. As one account of the Revolution has it:

In January 1776, political theorist Thomas Paine made explicit the connection between a written declaration of independence and a potential military alliance in his smash bestseller, Common Sense. “Every thing that is right or natural pleads for separation,” he implored. “‘TIS TIME TO PART”. Neither France nor Spain would be willing to help out British subjects, he warned. “The custom of all courts is against us, and will be so, until, by an independence, we take rank with other nations.”

* * *

The very idea of a document to formally declare independence was unprecedented; no previous nation which had rebelled against its mother country, as the Dutch Republic did against Spain over a century earlier, needed to announce its intentions in written form.2

Thus, while the Declaration of Independence was, first and foremost, documentary evidence of America’s new sovereignty, it was also a plea for help made by one country, however fledgling, to two potential allies of equal legal stature. Indeed, no sooner had the ink dried on the Declaration than did Congress “place[] copies aboard a fast ship bound for France, with instructions for Silas Deane, the American envoy in Paris, to ‘immediately communicate the piece to the Court of France, and send copies of it to the [Court of Spain]’.”3

C. Intrinsic Sovereignty

Intrinsic sovereignty refers to the state of governance within a country and is the form of sovereignty likely to come to mind first when sovereignty is brought up. Dictionary definitions of sovereignty generally concern intrinsic sovereignty, and a literal reading of them hints at issues that arise with intrinsic sovereignty.

Again, here is the definition of sovereignty from Black’s Law Dictionary, but this time with emphasis on that part of the definition relating to intrinsic sovereignty:

The possession of sovereign power; supreme political authority; paramount control of the constitution and frame of government and its administration; the self-sufficient source of political power, from which all specific political powers are derived; the international independence of a state, combined with the right and power of regulating its internal affairs without foreign dictation; also a political society, or state, which is sovereign and independent [emphasis added].1

“Supreme political authority” and “paramount control” are the language of would-be tyrants, which thus hang like a Sword of Damocles even over constitutional governments, which must perforce be implemented by human hands.

Historically, of course, that very issue was particularly acute since the sovereign power of nearly all countries took human form, such as a king. It is not surprising, then, to observe the progressive whittling back of powers that were viewed as within the proper ambit of sovereign power.

Definition and Scope of Intrinsic Sovereignty

For early English thinkers like Thomas Hobbes (1588–1689), living as they did in a monarchy, it is not surprising that the concept of sovereignty within a country or region began with a single person whose supreme power over everyone else was basically unlimited; the law was for all intents and purposes whatever the sovereign said it was.

For the society under a single human sovereign free from restraint or limitation, this created obvious dangers that begged for any number of remedies.

Limited Powers of a Sovereign—American and British Versions

Roughly fifty years after Hobbes, John Locke (1632–1704) began to seriously whittle away at the model of a sovereign with absolute power. While both Hobbes and Locke were highly influential on the colonists, it was Locke whose writing undisputedly resonated most strongly. In Locke’s writings we find any number of notions that gained a permanent foothold in the U.S. Constitution:

- First, that a government and not a person should be the sovereign.

- Second, that the government’s legitimacy hinged on the consent of the governed.

- Third, that strict limits should be placed on the sovereign government.

- Fourth, that sovereign powers should be dispersed among different areas controlled by a constitution.

- Last, and most radically, that the sovereign government itself should be held accountable for acting in a manner that violated the consent of the governed generally, and in particular, for violating an individual’s rights.

This latter theory of Locke’s—that of denying (or sharply limiting) the legal protections of sovereign immunity to the rulers themselves—is one that would resonate literally for centuries in the United States, rearing its head in the Constitution (impeachment provisions), throughout the Watergate episode, and even in the wake of the global financial crisis, as we shall see.

Both Britain and the U.S. Constitution (1787) reflect Locke’s teaching to varying degrees, but with crucial differences.

On the one hand, Britain, following the English Civil War (1642–1651) and the glorious revolution, had, in 1689 with the Bill of Rights, dispersed sovereign powers in accordance with Locke’s fourth provision. At that point, Parliament was vested with several important sovereign powers, including taxation, oversight authority for elections, and most importantly, statute-making (with no veto power available to the Crown).

On the other hand, though, members of Parliament (MPs) and Lords alike were legally protected by parliamentary privilege. On that score, executive power in Britain remained with the monarch even after the Bill of Rights. And the monarch’s immunity from the law was essentially absolute.

The best expression of Britain’s legal version of sovereign immunity is found in William Blackstone’s four-volume Commentaries on the Laws of England (1765), which summarized the totality of English law at the time and was the first legal treatise ever written. In volume 2, chapter 17, Blackstone states:

That the king can do no wrong, is a necessary and fundamental principle of the English constitution; meaning only, as has formerly been observed, that, in the first place, whatever may be amiss in the conduct of public affairs is not chargeable personally to the king; nor is he, but his ministers, accountable for it to the people: and secondly, that the prerogative of the crown extends not to do any injury; for, being created for the benefit of the people, it cannot be exerted to their prejudice.

In other words, the Crown was created for “you people,” so if anyone has a beef with the kingdom, he can take it up with the king’s ministers, because the king himself can do no wrong as a matter of law. Blackstone goes on to offer up a host of alternative villains available to step into the king’s shoes whenever the need for royal legal deflection might arise, the ersatz bogeymen having names like “misinformation” and “inadvertence”—all notable for the lack of any human party to whom liability could be attached.

Nevertheless, with the advent of free elections, Britain had adopted largely the same model of popular sovereignty that was to find expression in the U.S. Constitution. There were major differences, of course; for instance, the American power of the judiciary to not only interpret the laws but order both the legislature and the executive to enforce those laws has no equivalent in English law.

But for our purposes, the biggest difference pertains to sovereign immunity concerning the executive. While the Constitution left open the question of whether a sitting president could be sued or indicted, it essentially declared open season in other respects. Not only could a president be impeached while in office, but the Federalist papers had made it clear that once a president’s term ended, he could be indicted for crimes committed while he was seated in the White House. Moreover, as the Supreme Court made clear during Watergate, the president could be investigated for crimes while he held office.4

The Rule of Law

While the phrase “the rule of law” wouldn’t really take hold until the 19th century (with the 1885 publication of Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution by British jurist A.V. Dicey, who also had much to say about sovereignty), and while the principle itself dates back to, and is reflected in, the Magna Carta (1215), it was really the American colonists who cemented the principle of the Rule of Law, over and above the teachings of John Locke, as they grappled with creating the U.S. Constitution.

The tightest summary of what the Rule of Law is appears in the constitution of Massachusetts, written in 1779 by John Adams:

In the government of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, the legislative, executive, and judicial power shall be placed in separate departments, to the end that it might be a government of laws, and not of men [emphasis added].

There is tremendous economy in Adams’ formulation of the Rule of Law in two distinct and crucial respects.

First, when it comes to a country’s governance, there are only two items on the menu: either you can be ruled by men, or you can be ruled by law; there is no third option.

Second, if you choose to be a government of laws, that means no one is above the law; someone occupying a position above the law (say, for example, a king who “can do no wrong” as a matter of law) in a nation of laws represents an internal inconsistency and is really just the rule of man in disguise.

That Adams would formulate the phrase in 1779—just three years after the Declaration of Independence—is no accident. The Declaration is replete with petitions to both Parliament (many made by the colonies’ able ambassador, Ben Franklin) and King George III alike that had been denied; the colonists’ frustration crackles just beneath the surface of the entire document. Adams’ “government of laws, not of men” signals that in the U.S., appeals and petitions would be made not to any supreme ruler, but to principles of law, which reigns over all men.

For the Rule of Law to be truly effective, however, there are a handful of logical provisions that must obtain:

- The law must be supreme over not only all men, but over the government as well.

- The law must be clear and embodied in documentary form so there is no question as to its provisions or their scope.

- The law must be publicized and applied equally so that the playing field is even.

- The equal application of law extends not just across people, but time; legal precedent is crucial; the same fact pattern should produce the same result regardless of who is involved, or when.

- Citizens must consent to the law, which in turn must guarantee their fundamental rights.

- Laws not made in accordance with these provisions are void.

These principles of the Rule of Law run throughout the U.S. Constitution, which also provides for the administration of government and is the ultimate source document for all U.S. law.

The Role of Intrinsic Sovereignty in the Run-up to the American Revolution

In reality, intrinsic sovereignty (or self-governance) was the entire grist of the American Revolution. The Crown of Great Britain was sovereign within the American colonies, not the colonies themselves, despite their needs and demonstrated abilities for self-governance. While the state assemblies routinely passed and enforced their own laws, they did so at the indulgence of Great Britain. Whenever there was any conflict between colonial laws and practices, on the one hand, and the laws of the mother country, on the other, the Crown did not hesitate to dispatch enforcers to impose her will and suppress that of the colonies. This was a source of great conflict between the colonies and the Crown.

Though it took many decades, this conflict escalated to a flash point long after a great number of colonists had come to deeply resent the stream of abuses that had its provenance in overseas authority. It’s difficult to find a more succinct summary of the overarching conflict than that in the Declaration of Independence itself: “whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these Ends [Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness], it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government.”

A significant majority of the 27 complaints recited in the Declaration fall into one of two categories: legislative and executive.

Complaints of Legislative Abuses

Fully the first six grievances in the Declaration are directed at the king’s interference with the colonies’ efforts at law-making (thereby anticipating the Constitution’s provisions for law-making in Article 1 eleven years later). The following bullet points are direct quotes:

• He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public Good.

• He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing Importance, unless suspended in their Operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them.

• He has refused to pass other Laws for the Accommodation of large Districts of People, unless those People would relinquish the Right of Representation in the Legislature, a Right inestimable to them, and formidable to Tyrants only.

• He has called together Legislative Bodies at Places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the Depository of their public Records, for the sole Purpose of fatiguing them into Compliance with his Measures.

• He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly Firmness his Invasions on the Rights of the People.

• He has refused for a long Time, after such Dissolutions, to cause others to be elected; whereby the Legislative Powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the Dangers of Invasion from without, and Convulsions within.

The Declaration then lists a series of complaints about judicial matters and law enforcement before circling back and adding two more legislative abuses:

• For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws, and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments

• For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with Power to legislate for us in all Cases whatsoever

It is notable that the first three grievances all complain of the king’s refusal to assent or otherwise agree to laws passed by the colonies. The Declaration is silent with respect to particulars about the would-be laws involved; it was a generalized complaint, after all.

The Role of Healthy Fear

One of the best presentations on the Rule of Law, in this author’s opinion, was given by Glenn Greenwald at Yale Law School in 2013. The first 30 minutes, in particular, are outstanding. At the 28:15 mark of the video, Greenwald makes a crucial observation as to what breathes life into the Rule of Law as a practical reality, namely, fear. His words are worth considering in view of the current crop of leaders, both in and out of government, and our own interactions with them.

In a free and healthily functioning political culture, people who wield power do so with great fear of the consequences of what will happen if they abuse that power. They fear the people over whom they’re exercising that power. The fear they have of abusing their power might be legal—they fear that they’re gonna be investigated or prosecuted. It might be reputational—that they’ll perceive or fear that they will live in disgrace and shame if they abuse their power. It may be physical—that they fear that they will be attacked or even killed. But some necessary, healthy fear has to reside in the heart of those who wield power about the consequences of what will happen if they abuse power in order for our society to be free.

And in a tyrannical society, the exact opposite framework happens, which is that those over whom power is wielded fear their government, fear the people who are the most powerful factions in the society because they know that that power can be exercised without constraint. And I think that latter dynamic is the one that now prevails when the American citizenry thinks about how they relate to their government and to those who are most powerful in the society. It’s a climate of fear that has been cultivated and sustained by virtue of powerful factions being able to operate without constraints [emphasis added].

Monetary Authority as Part of Sovereign Power

Alexander Del Mar, the prolific 19th-century monetary historian and the first head of the Bureau of Statistics, explains at great length and over many papers and in many books that the root of the colonies’ troubles with the Crown boiled down to money. Del Mar contends that most American colonists were actually not in favor of breaking off from Great Britain, arguing that they merely wanted to keep their own monetary system separate from that of the Crown. No matter how heartfelt such leanings may have been, however, they are legally inconsistent, as monetary authority is an inherent part of sovereign power (and a jealously guarded part, at that).

To understand the grist of the controversy between Great Britain and the colonies, though, requires a bit of background.

The official monetary system of Great Britain (ignoring for the time being the paper currencies issued by various colonies) had a major tendency to create depressions within the colonies, according to Del Mar: “the Mercantile system of Great Britain… encouraged the import and discouraged the export of the precious metals from England. Therefore, unless the North American colonies could produce these metals from their own soil, which happily for posterity they could not, they had to be contented with such money as the Crown chose to provide them with.”5

To comprehend why precious metals had a tendency to be hoovered up from the colonies into London, it helps to understand that Great Britain had unleashed a debt-based monetary system on steroids in 1704, which basically allowed British banks to write IOUs (bills of exchange) that circulated as money. That year, Parliament passed the Promissory Notes Act of 1704, which allowed for the negotiability of debt; bank IOUs, which had previously been enforceable only as between the issuer and the recipient, became freely tradable.6

For example, if Grimsley were in possession of a £10 note issued by Bank A, which had issued the note to Lloyd, Grimsley could go to Bank A, at least once the 1704 Act was passed, and demand gold in the amount of £10. Before the Promissory Notes Act of 1704, courts would not necessarily enforce an IOU issued to one party as against another party; such courts considered a debt as a private matter between two parties and only enforceable as such. Enforcement of third-party debts like that was not uniform. Thus, in our example, Lloyd’s IOU from Bank A would not be worth anything to Grimsley under that view of the law.

The Promissory Notes Act of 1704 ended all that by providing for the third-party enforcement of IOUs issued by banks. Additionally, and as a matter of practice, banks began honoring not only their own IOUs (no matter which of their customers held them) but also honored IOUs issued by other banks. This was because, first, by honoring one another’s IOUs, the banking fraternity as a whole stood to become very wealthy by way of an ever-increasing money supply in which the fraternity itself would become the main supplier. Second, any imbalance of IOUs as between two banks could be settled at some predetermined time later, in gold.

Not surprisingly, the supply of bank-money IOUs exploded in the early 1700s, which would have pulled up the demand for precious metals to settle debt-money IOU transactions right along as well.

The story across the Atlantic, however, was fundamentally different.

For their part, the colonies had no private banks at all, and thus no institutions to issue IOU money in the first place. Indeed, the first private bank in America wouldn’t appear until 1781, and even then only in the form of a central bank, namely, the Bank of North America.7

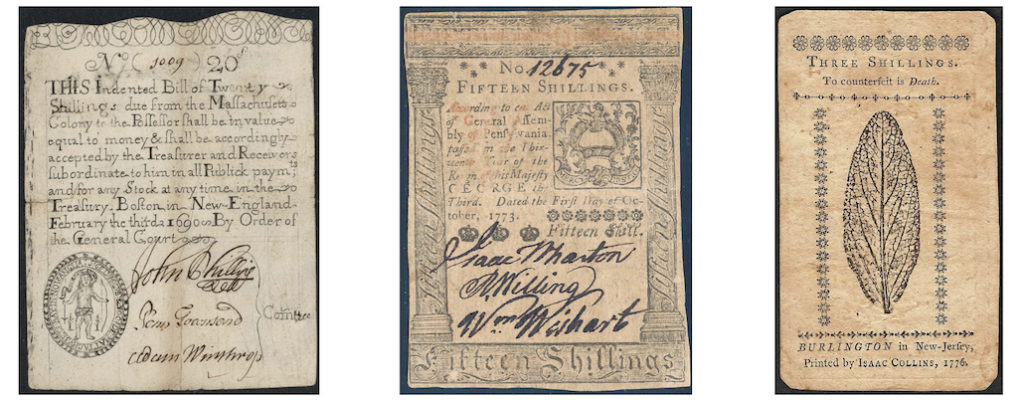

By 1750, Del Mar relates, the colonies experienced a huge “Contraction” [of Crown-sanctioned money, i.e., a depression]. Consequently, the colonies—unable to mine gold themselves—tried improvising their way around the lack of gold with an impressive array of alternatives ranging from silver to pine cone money. But far and away the most popular alternative currencies (which were issued individually by the colonies) were paper notes and bills of credit. Massachusetts had been the first to issue a paper currency in 1690.

In short, the decades leading up to the American Revolution featured two very different forms of money in the colonies: private debt-money issued by banks (having been implicitly licensed by the Crown to exercise its sovereign monetary privilege) and public money issued by individual colonies (which legally represented a usurpation of British sovereign authority).

In the ongoing monetary tug of war, the Crown had again and again suppressed colonial moneys, and to be clear it was doing so on behalf of London bankers:

But the narrow-minded and selfish London merchants and bankers, who influenced the government at this period, would not permit the colonies to have their own monetary system; they must accept such “national” coins as the London merchants chose to lend them; as though there was anything “national” about coins which were manufactured at their own (the merchants’) private behest and could be withdrawn, melted or exported at their own pleasure. Accordingly orders were sent to America to put down the Colonial money and enforce the falsely-named “national,” but really private money.8

According to Del Mar, the final straw for the colonists in the ongoing battle of currencies was the Stamp Act of 1774, “which required a stamp to be placed upon every instrument of commerce, and thus threatened to suppress or defeat the restoration of the paper money system which was at that time being sought, [and] the bitterness of the Colonists grew to phrenzy….”9

The opening move in what was to become the Revolutionary War was the response by the colonies to the Stamp Act:

Almost the first act of the Massachusetts and the Continental revolutionary assemblies was the emission of paper money in the teeth of the Royal prerogative, and this was done while yet the Colonies had no fixed determination of separating from the mother country. Indeed, barring Lexington and Concord, which were mere skirmishes to protect some trumpery stores, the emission of paper money was the first act of open resistance and defiance which the American Colonies offered to the Crown.10

At that point, Del Mar tells us, there was no turning back:

But, although the Colonies were as yet uncertain of their course with respect to separation, there was no uncertainty with regard to their monetary system. This they had determined should be independent of the Crown and this determination they had expressed in overt acts that had long marked them as disaffected rebels and were now to mark them as outlaws.

Lexington and Concord were trivial acts of resistance which chiefly concerned those who took part in them and which might have been forgiven; but the creation and circulation of bills of credit by revolutionary assemblies in Massachusetts and Philadelphia, were the acts of a whole people and coming as they did upon the heels of the strenuous efforts made by the Crown to suppress paper money in America, they constituted acts of defiance so contemptuous and insulting to the Crown that forgiveness was thereafter impossible.

After these acts there was but one course for the Crown to pursue and that was, if possible, to suppress and punish these acts of rebellion. There was but one course for the Colonies; to stand by their monetary system. Thus the bills of credit of this era, which ignorance and prejudice have attempted to belittle into the mere instruments of a reckless financial policy, were really the standards of the revolution. They were more than this: they were the Revolution itself!11

Complaints of Executive Abuses

The Declaration complains of three separate abuses involving the military, for example, “quartering large Bodies of Armed Troops among us.” That’s not too surprising given popular accounts of the American Revolution, in which ostentatious redcoats parade around in town squares like they own the place, to great tut-tutting followed up with teachings about the constitution’s limitations on the military.

The far more common colonial complaint about executive power in the Declaration, though, is of outright crime by the Crown. On this score, it isn’t so much abuses by an otherwise lawfully authorized power like the military that feeds the drive for separation, it is the outright criminality of the sovereign power itself. The king obviously saw himself as occupying a legal space above the law itself.

In the following list, only the last five items appear consecutively in the Declaration. The king’s crimes listed here may be thought of as the colonists’ answer to Blackstone’s legal pronouncement that “the king can do no wrong.” They likewise reinforce the Lockean notion that the sovereign himself should be held to account:

- For protecting them [armed troops], by a mock Trial, from Punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States:

- For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended Offences:

- He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us.

- He has plundered our Seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our Towns, and destroyed the Lives of our People.

- He is, at this Time, transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the Works of Death, Desolation, and Tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty and Perfidy, scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous Ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized Nation.

- He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the Executioners of their Friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands.

- He has excited domestic Insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the Inhabitants of our Frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known Rule of Warfare, is an undistinguished Destruction, of all Ages, Sexes and Conditions.

III. Sovereign Powers of a Nation

A. Introduction

There are any number of powers that a sovereign may wield. The U.S. Constitution recites a whole host of such powers, for example, taxation.

The history of the United States, however, has revealed that two sovereign powers in particular, unlike the others, are absolutely essential to the country’s sovereignty, namely, the power to coin and the power to enforce laws. These two sovereign powers are briefly described here (in Section III) before their critical importance to national sovereignty is set forth and shown in subsequent sections.

B. General List of Sovereign Powers

The U.S. Constitution reflects any number of sovereign powers, which are distributed among three branches of government. The Constitution, however, places limits on governmental power. That fact alone signals the unequivocal rejection by the founding fathers of any Hobbesian notion of a sovereign having absolute power over his subjects.

But the founders take matters a step further. Rather than merely recite various constitutional limits that cut back on the power of a sovereign government, they instead start from the supposition that, since all men are free and equal, the sovereign government possesses only those powers that are specifically called out and allocated to the sovereign. If a power isn’t thus at least generally allocated by the Constitution, then the sovereign government simply does not possess that power.

This conflicts with the erroneous notion—sadly prevalent to this day—that the Constitution is a source of positive rights of the people. Under this model of the Constitution, we the people have the right to free speech and free assembly because the First Amendment granted us that right.

That concept of the Constitution has things exactly backwards. The truth is that “we the people” (the first three words in the Constitution) are the sovereign, and our government has only those powers that are consented to and granted to it by us. The First Amendment, to elaborate on the previous example, doesn’t give us any rights at all; instead, it stakes out a bit of territory where the sovereign government may not trespass now and may never trespass, absent an express amendment to the Constitution (which, of course, the Constitution makes exceedingly difficult).

By way of that background, the Constitution makes reference to at least the following sovereign powers:

- Passing laws

- Conducting elections

- Punishing and expelling members of Congress

- Providing for the common defense

- Entering into treaties with other nations

- Raising revenue

- Collecting taxes, duties, imposts, and excises (so long as uniform)

- Paying debts

- Borrowing money on the credit of the U.S.

- Regulating commerce with other nations, with Indian tribes, and between states

- Establishing uniform laws throughout the U.S. regarding bankruptcies and naturalization

- Resolving disputes between citizens and states alike

- Coining and regulating money

- Punishing counterfeiters

- Establishing a post office

- Establishing standards for weights and measures

- Issuing credit

- Declaring and waging wars

- Raising armies

- Calling forth the militia

- Commanding the Army and Navy as well as militia

- Granting reprieves and pardons for offense against the U.S. (excepting impeachments)

- Executing the laws

- Resolving cases and controversies

- Conducting jury trials of all crimes except impeachment

C. The Two Most Crucial Powers of Sovereignty

There are two powers above all others that a sovereign must retain for itself by law if it wishes to remain sovereign in fact: money issuance and law enforcement. Indeed, and along these lines, there has been an historical debate, loosely speaking, over the most important power that a sovereign can have. Generally speaking it comes down to two powers: money and force.

For Machiavelli, the most important sovereign power was simply raw force (“steel”). In Art of War (1520), he writes:

Men, steel, money, and bread, are the sinews of war; but of these four, the first two are more necessary, for men and steel find money and bread, but money and bread do not find men and steel.

Three centuries later, however, Thomas Jefferson took essentially the opposite position:

Banking establishments are more dangerous than standing armies.12

Notably, the period between Machiavelli and Jefferson was one of tremendous changes, including the establishment of private banks of issue—both retail banks and central banks. The first central bank in the world was the Bank of Amsterdam, established in 1609, though it was not technically a bank of issue (meaning it trucked in precious metals and did not issue its own credit).13 The first central bank of issue in the world was the Bank of England, established in 1694.14

The Bank of England was allowed by law to issue bank notes utterly without restraint:

The Bank was allowed to create bank notes in an amount equal to the money it lent the Government. This is another way of saying it could use government debt as its reserves or collateral. For example: the Crown wants a loan from the Bank; the Bank has no money of its own, but creates money for the loan out of thin air, based on the reserve asset of the Crown’s resulting debt to it.15

Given the unfettered ability to issue money, it is perhaps not surprising that the Bank of England had to suspend note issuance in 1696, just two years after its founding.16

In any event, there is little question that the dual powers of money-creation and force are of paramount importance to any sovereign government. As one author has it: “Whoever controls the issuance and first use of money, as well as the main pathways of its allocation, is in possession of the most powerful instrument of societal control other than command power based on the legal authority to issue directives backed by force.”17

But there is more to money creation and force than simply as a pair of contestants clocking in as winner and runner-up in a sovereign beauty contest, and it is a mistake to view the pair as separate or freely divisible. Instead the relationship should be thought of as one of mutualism, with money creation enabling the establishment of force, which in turn protects the institution of money creation.

The experience of the colonies throughout the Revolutionary War bears out this observation.

The recent and rapid descent of the U.S. into lawlessness likewise speaks to the essential nature of money issuance and law enforcement, as we shall see later. We next turn to money creation and law enforcement separately.

Money Issuance (Creation)

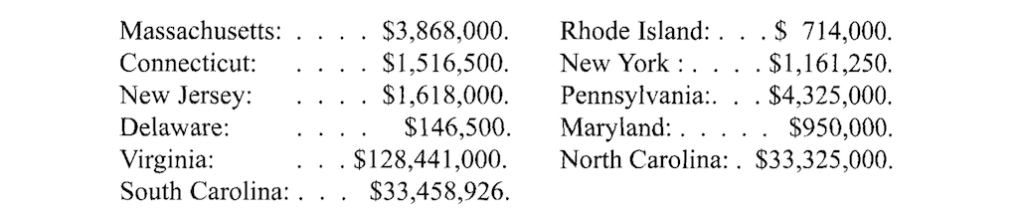

The rapid depreciation of the colonial Continental—the paper currency issued during the Revolutionary War—is often cited, almost reflexively, as an example of the perils of fiat money. And indeed, at first blush that line of thinking seems to be borne out by the historical record—at least the depreciation part:

In March 1778, after three years of war, it was $2.01 Continental for $1 of coinage. At the end of 1778 the Continentals retained from 1/5 to 1/7 of their value against coinage. At the end of 1779, they retained only 1/25 of their value against coinage (4%). By May 1780, the currency stood at 1/75 and coinage in Massachusetts and 1/120 in Pennsylvania. Still it continued. This massive British counterfeiting of the Continentals is ignored by the advocates of private money or commodity money. The British, and just plain crooks, also counterfeited great amounts of the state currencies.18

The depreciation of the Continental, however, was not due to the fact that it was a “fiat currency.” Indeed that version of events has matters pretty much exactly backwards: what killed the Continental was the fact that it was not a fiat currency, meaning: it was issued without any legal backing whatsoever. Thus, to whatever extent the colonies possessed the force to back up their collective currency, such force was mere futility in that there was no law to enforce in the first place. The Crown took full advantage of its enemy’s legal predicament in this regard, and pounded the Continental into oblivion—by counterfeiting it with wild abandon.

While Del Mar is correct that “[a]lmost the first act of… the Continental revolutionary assemblies was the emission of paper money in the teeth of the Royal prerogative,” elsewhere he informs us that there was no legal authority behind such money: “The Colonies did not clothe the Continental Congress with power over money, but retained it themselves.”19

Del Mar spells out the specifics of the problem as follows:

The Continental Congress had no legal power to create money and no physical power to maintain or enforce its circulation after it had been created. It could not redeem the notes in taxes. Congress was a revolutionary body liable to be suppressed at any moment. It was without any legal authority, either from Great Britain or from its constituent States, to create money. This power was first granted by the Articles of Confederation, which although they were provisionally agreed upon in 1777 were not ratified by all the states until 1781, by which time the Continental bill system was superseded by coins.20

By 1781, of course, Cornwallis had surrendered, all but ending the war then and there.21 In the interim, though, the value of the Continental had plummeted by as much as 99%. This was due to British counterfeiting, however, not to the untrammeled emission of money by the Continental Congress.

Law Enforcement

The British penchant to use massive counterfeiting as a means of prosecuting wars was so common that historians took note of it. “The English government which seems to have a mania for counterfeiting the paper money of its enemies entered into competition with private criminals.”22 So confident were the British in this monetary line of attack that they ran an advertisement in a New York newspaper in April 1777 offering for purchase—using a public venue—counterfeit Continental bills for no more than the cost of the paper they were printed on:

Persons going into other colonies may be supplied with any number of counterfeit Congress notes for the price of the paper per ream. They are so neatly and exactly executed that there is no risque in getting them off it being almost impossible to discover, that they are not genuine. This has been proved by bills to a very large amount, which have already been successfully circulated. Enquire for Q.E.D. at the Coffee House, from 11 P.M. to 4 A.M. during the present month.23

An endless rash of predicable results ensued, with some notable examples: “In April 1780, two British ships—the Blacksnake and the Morning Star—were captured off Sandy Hook with a large amount of counterfeit on board.”24

By 1780, the situation seemed almost hopeless. As described by Tom Paine, “the treasury was money-less and the Government credit-less.” Over the next year, private donations were sought, and the Bank of North America—the nation’s first central bank—was set up. Quite notably, however, it was the French government, not America’s central bank, that saved the day: “by October 1781, only $70,000 had actually been paid in [to the Bank of North America], when a French frigate arrived with $470,000 in coinage.”

In sharp contrast with the American failure to punish any of the massive counterfeiting of the Continental, a failure that stems at least in part from the Continental’s lack of legal status, England did not hesitate to punish counterfeiters—and even people found guilty for so much as clipping (shaving down) the coin of the realm—with death.25 Notes Zarlenga: “There was [in 1690] a £40 reward for denouncing a clipper, and the clipper could go free if he denounced two more clippers. Hangings were held regularly. On just one day, seven men were hanged and one woman burned at the stake for coin clipping!”26

IV. The Disaster of Private Money (Debt-Money) Issuance

A. Introduction

In Article 1 of the U.S. Constitution, Congress is granted the power “[T]o coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin, and fix the Standard of Weights and Measures” (U.S. Const., art. 1, § 8, ¶ 5). Separately, the Constitution forbids states to “coin money” and to “emit Bills of Credit” (U.S. Const., art. 1, § 10, ¶ 1).

Thus lacking the power to issue credit and possessing only the power to coin money, Congress should be—but is not to any material degree—in the business of coining money. But that is not the case, with the immaterial exception of coins, which the U.S. Treasury mints under congressional authorization.

Consequently, there is an enormous constitutional void in the U.S., where one should find government-issued money (“coin”) but where instead one finds privately issued credit. And therein lies what is the most fundamental affliction in the United States, which is almost never discussed due to the enormous value of the private credit-issuing franchise that has filled the empty money shoes left by congressional inaction.

To understand the massive extent of this fundamental problem, however, one must first understand the difference between real money, on the one hand, and its havoc-wreaking substitute—credit, or debt-money—on the other hand. To this end, we include three sections.

First, we distinguish between real money and debt-money. Second, we point out several intractable problems that are inherent to debt-money. And finally, we discuss some real-world problems to debt-money, briefly including the massive Missing Money problem brought to light by Solari’s extensive work on that topic.

B. Real Money vs. Debt-Money

In the U.S., the difference between real money and debt money can most easily be explained by referring to the money that’s used in ordinary retail transactions billions of times every day.

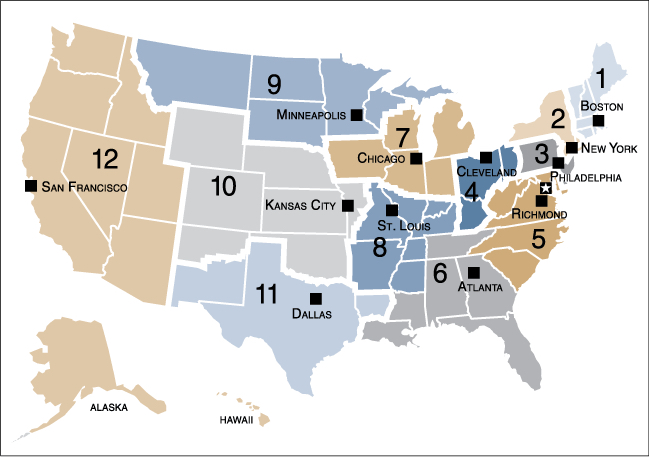

Coins are real money. Coins are minted by the U.S. Treasury and sold at face value to the Federal Reserve, which distributes coins into the U.S. monetary system by selling them to banks, again at face value. The profit on coins, formally known as “seignorage” (i.e., the difference between the face value and the cost of the coins), accrues to the U.S. Treasury.

Cash (or Federal Reserve notes) is real money as well, but with a twist: the creation of cash requires debt (historically and typically, a U.S. bond) in an amount that corresponds to the face value of the cash. Cash is issued by the twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks, which book cash as a liability and are required to pledge adequate collateral in a matching amount. The Fed books that matching amount of collateral as an asset. Before the 2008 crisis, the liability side of the Fed’s balance sheet was almost entirely made up of cash, while the asset side of the balance sheet consisted almost entirely of U.S. Treasury securities (or bonds, i.e., debt).27

Coins and cash are real money because they can extinguish any debt without the creditor’s consent: once tendered to the creditor in payment of a debt, that debt is no longer enforceable in court. In other words, coins and cash are legal tender (see definition in next section, “Real Money Is Legal Tender, Debt-Money Is Not”).

Electronic money in bank accounts is debt-money, not real money. Electronic bank money gets created by banks when they make loans, and destroyed when the principal of those loans is paid back. The sum total of electronic bank money on a given day is thus the total amount of electronic bank money the previous day PLUS the amount of new loans made by banks on that given day MINUS the amount of principal paid back on loans that same day.

By way of that background, let’s consider three differences between real money and debt-money.

Real Money Is Legal Tender, Debt-Money Is Not

Blacks Law Dictionary offers the following definition of legal tender:

Lawfully established national currency denominations. Legally required commercial exchange medium for money-debt payment. Differs widely from country to country. Creditors, lenders, and sellers retain the option to accept financial vehicles, such as checks and postal orders that are not legal tender, for payment of debt. Also known as lawful money.28

Under U.S. law, only coins and cash are legal tender:

United States coins and currency (including Federal reserve notes and circulating notes of Federal reserve banks and national banks) are legal tender for all debts, public charges, taxes, and dues. Foreign gold or silver coins are not legal tender for debts.29

Legal tender, as already noted, is money that extinguishes debt as a matter of law—even if the creditor rejects the tender offer. One purpose of legal tender is, in fact, to deny creditors the ability to keep debtors indebted to them in perpetuity: once the debtor tenders legal money, the debt gets extinguished, full stop.30

As the legal dictionary definition states, “creditors retain the option to accept financial vehicles, such as checks and postal orders that are not legal tender, for payment of debt.” But the reverse is true, too, and it can be a trap for the unwary: creditors can (absent some agreement to the contrary, of course) reject offers to pay off debts that are not made in legal tender.

It is the law pretty much throughout the world that bank account “money” is debt-money and as such does not fulfill the legal requirements of money, as a leading legal treatise on the international laws on money makes clear.

As a rule… the economist’s view that everything is money that functions as money is unacceptable to lawyers. Bank accounts, for instance, are debts, not money, and deposit accounts are not even debts payable on demand.31

If it isn’t really money at all, why is electronic money, then, treated as such seemingly everywhere? The same legal treatise supplies the one-word answer: consent. People consent to the use of electronic money, which has enormous traction as the result of ages-old commercial practice:

In the absence of the creditor’s consent, express or implied, debts cannot be discharged otherwise than by the payment of what the law considers as money, namely, legal tender. Nor can the important consequences of tender be achieved except by the offer of lawful money. Money is not the same as credit.32

Real Money Is Permanent and Safe, Debt-Money Is Temporary and Unsafe

Cash and coins are physical money that can be maintained and preserved for a very long time—if not forever, then certainly for the life of the holder.

All debt-money, in contrast, exists as a liability on a bank’s balance sheet.33 Thus, when money is deposited in a bank, the depositor no longer owns that money but instead becomes an unsecured creditor of the bank in the amount of the deposit. Consequently, if the bank goes under, that “money” is gone; at best, it is converted to a claim with the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) for reimbursement. Real money doesn’t need insurance.

Some monetary schools hold that all money is debt,35 with the leading example being Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). Perhaps it was so named because its “theory” is wrong on both the facts and the law. As a factual matter, the theory that all money is debt is simply false. A leading monetary scholar, Michael Kumhof, refutes the theory with numerous examples as follows:

There are in fact many instances of debt-free tokens performing this [monetary] function, ranging from cowrie shells in ancient China, to essentially worthless base metal money in early Rome, to the “truck” systems which existed in mill towns in Northern England in the early stages of the industrial revolution, to cigarettes in WWII prisoner-of-war camps.34

Indeed, Alexander Del Mar had refuted the theory himself numerous times several decades before Mitchell Innes even originated it.35 One of Del Mar’s most interesting examples of money that is not debt-based, and one to keep in mind as central banks rush headlong to implement central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), is as follows:

Slaves were used as money in Britain previous to the Norman invasion, in America during the early portion of the Spanish Conquest and the Repartimiento system, in Central Africa very recently, and in most primitive as well as in most decaying communities. Cattle have been used as money in all early pastoral communities.36

The theory that all money is debt is also wrong on the law, as we saw above in connection with legal tender (“[b]ank accounts, for instance, are debts, not money”). Additionally, it is precisely the different (superior) legal status of actual money (cash and coins) from debt-based bank-money that gives rise to a material risk carried by bank-money that does not apply to real money—the risk of bank default:

LEGAL TENDER AS A TRAP FOR THE UNWARY

Alfred Owen Crozier in U.S. Money vs. Corporation Currency (1911) provides an anecdote that illustrates exactly how legal tender can operate as a trap for the unwary:

Some western men had discovered and developed a valuable mine to a point where there was enough ore in sight to show to a certainty that the property was sound and of great value. They needed money to build a large plant and operate the property. They went to Wall Street. After careful investigation the New York “bankers” agreed to furnish the money. Instead of joining in the deal they put their money in as a “loan” secured by mortgage on the mine. It was made a short-term mortgage. It came due before the plant could be finished and operated to make the mine yield enough to pay the debt. Payment was demanded and the mortgage for about $150,000 foreclosed.

The western men finally raised the money elsewhere and on the last day of redemption tendered it to the sheriff in settlement. The eastern lawyer representing Wall Street people found that considerable of the $150,000 was gold certificates and some bank-note currency. These not being “lawful money” he refused the tender and demanded payment in “lawful money.” There was then no time to go from the distant county to a bank in a large city to get the necessary gold or greenbacks, the law for money. The western men thus were robbed of their property and the rich Wall Street sharpers got it, as was their aim from the beginning, for a mere fraction of its value. The legal-tender “joker” in the law enabled them to do it legally. Few people know that bank currency is not legal tender…

Alfred Owen Crozier, U.S. Money vs. Corporation Currency: “Aldrich Plan,” The Magnet Company, 1912, pp. 326-327.

The money of customers in a bank will never be safe as long as the money is a balance sheet position of bank debt, rather than being a customer asset in its own right off the banks’ balance sheet, like having coins in the pocket, notes in the wallet, or financial assets in a separate securities account that may be managed by a bank, but is not itself a bank asset or bank liability.… How can a monetary system be stable and reliable if even the existence of the money is unreliable?37

Real Money Has a Single Tier, Debt-Money Needs Two Tiers

The difference between real money and debt-money is also clear from the fact that debt-money, unlike real money, means there are two tiers of money: the first tier is real money, the second is debt-money. The second-tier nature of debt-money is inherent from the way it originated historically.

Debt-money first arose when goldsmiths created tablets for customers who bailed their physical gold with the goldsmith and needed evidence of as much so that they could reclaim their metal later. Eventually, the tablets themselves began to circulate as money rather than the gold itself; the tablets were easier to carry around, and with less risk of robbery. This in a nutshell was a two-tiered money system: real money (gold) and debt-money (tablets). As one monetary history has it:

When the tablet begins to circulate, there are two kinds of money in circulation: hard cash made of valuable metal, and bank-credit represented by clay tablets (equivalent to today’s bank notes).38

As this bit of history suggests, the two-tiered money system does not involve a relationship of equals. One tier is legally superior to the other. This has important implications for sovereignty.39

C. Inherent Problems of Debt-Money

Now that some differences between real money and debt-money have been explained, several shortcomings of debt-money that relate directly to issues of sovereignty are set forth here.

Debt-Money Is Confusing

The confusion over debt-money arises in large part from the notion and even the language of a “deposit” at a bank. Deposits are confusing because they can be created by a genuine deposit of cash or they can be created when a loan is made by a bank merely writing numbers into an account and loaning out these valuable numbers, which are treated the same way as cash.40 As Ivo Mosley put it in a 2020 book titled Bank Robbery:

Our money system is difficult to understand. It is counter-intuitive, so much so that a leading banking historian (Lloyd Mints) described it as a work of the devil.41

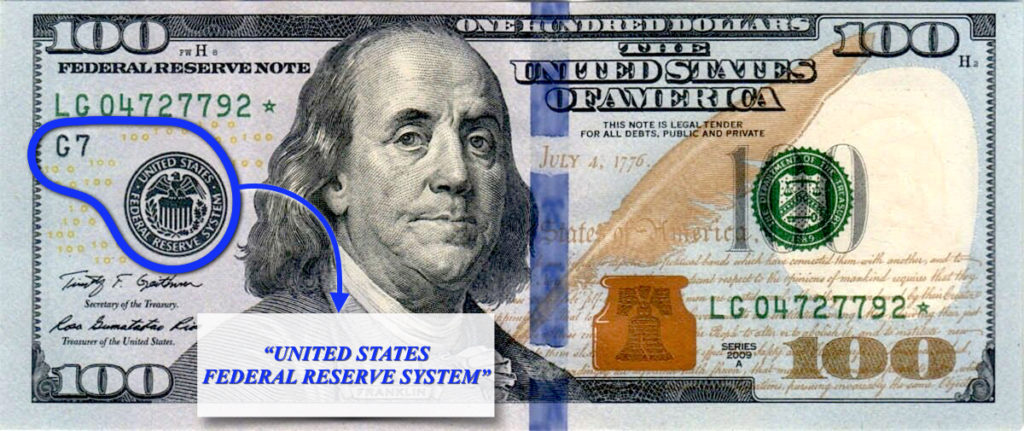

This confusion has important implications for sovereignty. The vast majority of people have no idea how the monetary system works, which inures to the benefit of the private banks that do the actual money-issuing in that system, namely, the Federal Reserve (actually, the twelve regional Federal Reserve banks issue the money; more confusion on display) and commercial banks.

As we saw in connection with the Declaration of Independence, consent is the linchpin of legitimate government in the U.S. But, by design, that consent is not informed consent. Would the Federal Reserve Act have passed if people really understood how the monetary system works? The same question must be posed about future monetary legislation as well, for example, the authorizing legislation that is highly likely to be needed for the Federal Reserve to issue CBDC.

Debt-Money Is Fraudulent and Usurious

The ability of banks to create debt-money out of thin air to purchase real assets was an issue that concerned some of the country’s founders. For instance, in a letter to Thomas Jefferson in 1814, John Taylor observed the following about debt-based money:

[It] possesses an unlimited power of enslaving nations, if slavery consists in binding a great number to labor for a few. Employed, not for the useful purpose of exchanging, but for the fraudulent one of transferring property, currency is converted into a thief and a traitor, and begets, like an abuse of many other good things, misery instead of happiness.42

What Taylor is getting at is the very real problem of usury, which is the extraction of money (or something of value) without supplying anything of real value in return. Usury is loosely thought of as “high interest rates,” but that’s not right, simply because high interest rates are fully justified where there is high risk. It’s thus the extraction of money without any proportionality of risk to the lender that leads to the “fraudulent transfers” that Taylor is talking about.

In this light, the purest form of usury may be found on the balance sheet of the Federal Reserve, where as of February 10, 2022, $5.73 trillion in U.S. Treasury securities (which pay interest) is counterbalanced on the liability side by $2.18 trillion in Federal Reserve notes and other monetary instruments that the Fed creates out of thin air that pay zero or near-zero interest.

Unlike commercial banks that create debt-money out of thin air, the Federal Reserve faces zero risk when it creates money this way. A commercial bank that lends a business $1 million faces the risk that the business might fail. If that happens, the $1 million liability on the bank’s balance sheet is now backed by a promissory note with a face value of $1 million but with a real value that is zero. To the bank, that $1 million mismatch between assets and liabilities must come out of the bank’s equity. That’s simply how balance sheets work: equity equals assets minus liabilities. If the bank’s equity goes negative, it is broke and must undergo resolution.

The Federal Reserve has no such risk. The “borrower” is the U.S. government, from which the entire legal authority to issue money derives in the first instance; it can’t fail. Looked at another way, if the U.S. (the borrower) does fail, it’s going to take down the creditor-Fed—the existence of which hinges in its entirety on the existence of the U.S.—with it.

Against that legal backdrop, it is clear that the privately owned Federal Reserve is receiving interest-bearing financial instruments (U.S. bonds) in exchange for creating “liabilities” that pay zero interest in the case of cash or near-zero interest in the case of reserves. The Federal Reserve system has the sovereignty relationship exactly backwards, profiting from the constitutional money-creating power that belongs to We the People by charging them interest.43

Debt-Money Is Contrary to the Rule of Law

Under the U.S. Constitution, money creation is an act of sovereignty: “Congress shall have Power… To coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin, and fix the Standard of Weights and Measures.”44 For this reason, the power to coin money should not be delegated to some citizens and denied to others. As Crozier stated:

Because creating money is an act of sovereignty, a function of government exercised only by means of the will of the people as expressed in the law, the issuance of money should not be farmed out or delegated by the Government to any private individual or corporation for profit or advantage. And for the same reasons this is true of any currency based on or issued under authority of law to be used in place of or as a substitute for money. Law and all benefits thereunder must be impartial and general for the good of all people without special favor or discrimination.45

What drives the need for impartiality of the law “and all benefits thereunder” is the Rule of Law. As presently configured, however, a tiny minority of people possess a sovereign power that is denied to everyone else. This flouts the principle under the Rule of Law that the same laws apply equally to everyone. Under the banking laws, the same behavior (money issuance) that profits one person will land another in prison for counterfeiting (or, more likely, one or more cyber crimes, since bank money is electronic).

Moreover, the same banking laws that inure to the benefit of bankers at the same time take money (property) away from everyone else in the form of interest payments on what ought to be, but is not, a public good, namely, money coined out of thin air. Again, we see the false notion that banks lend out pre-existing money operating to the benefit of bankers while the people paying for that benefit remain ignorant of it due to their erroneous perception of how banking works. As Mosley explains:

Because the debt from the bank is money, and money is valuable, it seems quite fair that we pay to borrow it. This hides the real injustice in the system, which is not the payment of interest. The real injustice spreads far and wide but begins with two simple facts: money is created out of nothing for profiteers, and the entire money system is rented out at interest.46

Debt-Money Inherently Causes Boom and Bust Cycles

As already noted, Alexander Del Mar observed in his History of Monetary Systems that “the commercial community has been subjected to alternate epochs of monetary contraction and expansion” ever since the sovereign prerogative of coining money was turned over to private banks.47

Of course, history has taught that turning money over to private banks results in a debt-based monetary system, since banks can then rent out the money supply at interest to generate profits from what is a public good under the Constitution.

To understand more fully how debt-based money is inherently unstable, it helps to track what happens when a debt is paid back. Generally speaking, when a debt is paid back, the bank to whom the debt is owed cancels the note (the borrower’s IOU), and money is destroyed. More specifically, though, when a debt is paid back to a commercial bank, the portion of the payment that goes to the principal of the debt is canceled, and money is thereby destroyed. In contrast, the portion of the payment that goes to interest on the debt simply changes hands (from the debtor to the bank, which can pay salaries, etc.), and no money is destroyed.

And of course, when a debt from a non-bank is paid back, the entire payment of principal and interest simply changes hands, and no money is destroyed, just as no money is created when a non-bank lends.

There are three drivers of instability; two are inherent in debt-based money while the third owes to human nature and is confirmed by history.

First, the payment of interest on money created as debt transfers wealth from the productive class to the rentier class of financiers. This leaves less money available to the productive class for the repayment of debts, on the one hand, while at the same time those debts are ballooning at the rate of interest (or even faster, due to fees and penalties—another wealth transfer), on the other hand. Over time, there is a pincer effect on the productive classes according to which farming was historically affected first, followed by manufacturing, followed by non-financial services—hollowing out the U.S. economy over the course of decades—until what’s left is a class of highly paid financier-gamblers and low-paid infrastructure workers. This is where we’ve been for some time, and it is getting worse. That inevitable deterioration of economic conditions is driven by, and indeed is a feature of, the debt-based monetary system.

Second, in a debt-based monetary system, there is an invisible ratchet wrench that increases debts at a materially faster rate than money can possibly be created—even if the interest rate is zero (which it never is, due to risk). The ratchet mechanism is this: while the creation of new money inherently creates new debt, new money is not necessarily created when new debt is created. The latter is due to the fact that non-banks lend according to the standard model, that is, simply transferring pre-existing money from lender to borrower. If Linda lends Kevin $100, the money supply doesn’t change (because Linda took the money from her pocket and handed it to Kevin rather than creating it), but the level of debt in the system increases by $100 (because Kevin added $100 to his debt load, but Linda did not reduce her own). The net effect is an economy operating as a pyramid scheme with debt outrunning money to pay down debt at hyperparabolic rates.48

The third driver of instability is plain old greed, coupled with the fact that bankers can profit directly from their control of the money supply. Crozier offers explanations and historical examples of this in his book opposing the creation of the Fed (then proposed as the “National Reserve Association”) and states:

Mortgages and bonds bearing a fixed interest rate are increased in value by contracting the supply of money because the fixed income then will buy more property and labor at the lower prices. The bulk of the vast bond or fixed income wealth of the world is owned by the banks and by other incorporated and individual holders here abroad. The banks of this country own bonds exceeding in value the total of all the money in circulation in the United States. This vast bond wealth would be greatly enhanced in value if contraction of the currency should make money scarce [emphasis added].49

Of course, such a contraction can be caused by banks simply not making new loans, on the one hand, and by banks calling in or otherwise canceling existing loans, on the other. The colossal conflict of interest Crozier describes is one of the main reasons he battled so ferociously against the proposed Federal Reserve Act (then called the “Aldrich plan,” after the prominent and very bank-friendly senator from Rhode Island):

The Aldrich plan would put the ownership, control and management of the National Reserve Association, with power to inflate and contract the quantity of money without limit, in the hands of the very private interests that would most profit by an abuse of that dangerous power. And every dollar gained by those interests through excessive inflation and contraction of the volume of currency would come out of the pockets of the people of the United States.50

Crozier discusses the financial panics of 1873, 1893, and 1907, contending not only that all of them were artificially created by Wall Street bankers but that they did so to further consolidate the power of the banks through means of congressional legislation. In the case of the 1893 panic, Crozier says it was to get Congress to repeal the Sherman Act in order to stop the U.S. government from issuing real money instead of debt-money—a panic that was effected by reducing loans:

An article in Pearson’s Magazine for March, 1912 by Allan L. Benson, makes public alleged important additional data designed to further prove that the banks deliberately caused the panic of 1893 for legislative purposes. It gives the following as a mandatory circular letter to all the banks alleged to have been sent by the National Bankers’ Association on March 12, 1893, eight days after Cleveland was inaugurated:

“Dear Sir:—The interests of national bankers requires immediate financial legislation by Congress. Silver, silver certificates and Treasury notes must be retired and the national bank notes, upon a gold basis, made the only money. This requires the authorization of $500,000,000 to $1,000,000,000 of new bonds as a basis of circulation. You will at once retire one-third of your circulation and call in one-half of your loans….”51