Wu Youru. Regaining the Provincial Capital of Ruizhou (1886). Private collection. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

The conventional wisdom that “law” and “justice” are not the same thing can be illustrated by works of art from any historical period. The painting above represents a battle between the Chinese Imperial army and the rebels from the Taiping Rebellion. The imperial soldiers, clad in blue and red uniforms, are chasing the rebels, who are fleeing a city that was besieged for over a year. The Qing empire represents here the state law that is crushing the resistance of the rebels, who, at least in part, were fighting in pursuit of social justice. The Taiping Rebellion, which lasted 14 years and left an estimated 20 to 30 million dead, is considered the bloodiest civil war in world history.

The Chinese population had rebelled many times against the foreign Manchurian Qing dynasty during its long reign (1644-1911), but the Taiping Rebellion that started in 1850 was unusual in that it was led by local Chinese people who were at the same time Christian Protestant converts. It was also the only anti-Manchurian rebellion that was originally assisted by foreign armies that occupied southern China. While the peasant Taiping rebels were fighting for social justice, political independence, and spiritual reform, the foreign occupiers were more concerned about preserving concessions they had obtained from the imperial government. When the Qing army started gaining over the Taiping forces, the foreign support swung to the imperial side.

The impressive scroll above is one of 67 painted for the Imperial palace hall during the reign of Qing emperor Guangxu, a puppet ruler living in the shadow of the empress dowager Cixi. The history of the late Qing dynasty is a history of never-ending conflicts between the native Han population and the Manchurian rulers, between the European invaders and Chinese people, and between the oppressive laws of the land and social injustice evident at every turn. This colorful imperial scroll illustrates the triumph of the state’s law over a rebellion that at least partly stemmed from insufficient justice. Yet within a few short decades of this scroll being painted, the Qing empire would disappear, and new political forces would pick up the fight for a new social order.

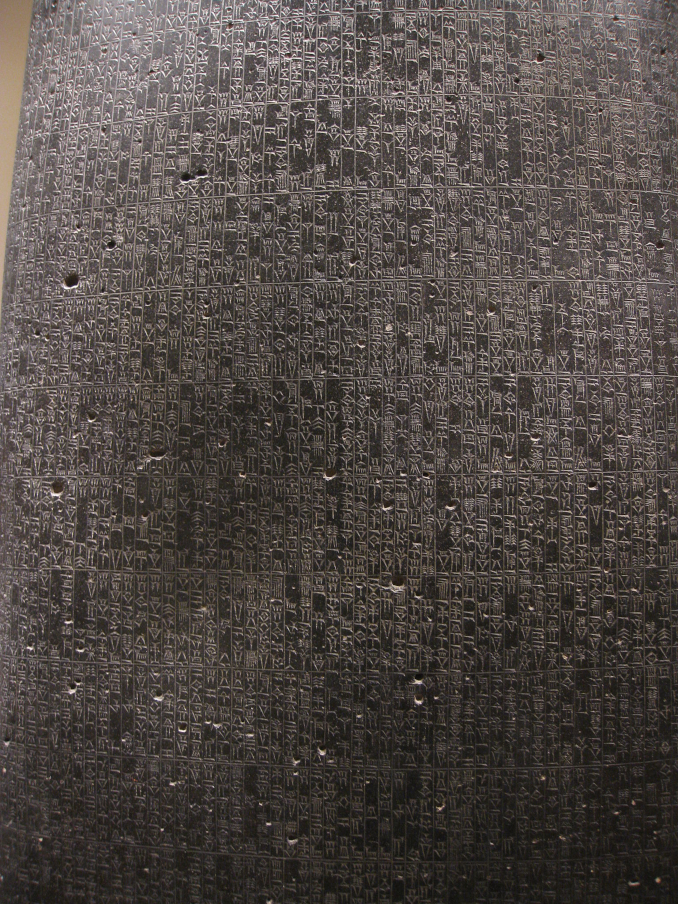

Text of Code of Hammurabi (c. 1791-1793 BC; discovered 1901). The Louvre. Photo: Deror avi/Wikimedia Commons

Through the present day, many systems of law in Western civilization are partially derived from the codices of two ancient rulers—the Babylonian king Hammurabi and the East Roman emperor Justinian—as well as the more modern conqueror, Napoleon Bonaparte. The laws and societies have changed many times since those rulers’ times, but the idea that relations between people need to be regulated by known and unified rules stems from those historic legal systems.

The Hammurabi code was created during the reign of an Akkadian ruler about 38 centuries ago.

Code of Hammurabi (c. 1791-1793 BC; discovered 1901). The Louvre. Photo: Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Wikimedia Commons

The text of the Code of Hammurabi, written in Akkadian, was recorded on a basalt stele in about 1791 BC, but it was not discovered until 1901 during the archaeological excavations of Susa (modern Iran). The Hammurabi laws deal with the same societal and individual prescriptions and proscriptions as our contemporary laws, covering areas such as property protection, marriage and inheritance rules, land ownership, commerce laws, and punishment for assault. The top of the black stone is decorated with a relief of King Hammurabi receiving the laws from Shamash, a god of justice, thus ensuring divine support to issue and execute the laws among his subjects. The bottom part of the stele has the engraving of the code’s text. Hammurabi’s code was preceded by much earlier Sumerian versions (the oldest tablet dating from 2100 BC), but his reign introduced the most comprehensive one. The original stele resides in the Louvre, while copies can be found at the United Nations in New York and the Pergamon museum in Berlin.

The East Roman emperor Justinian owes his lasting fame to commissioning the Hagia Sophia basilica, one of the most breathtaking architectural structures in history, but this emperor is also credited with gathering and issuing a system of laws. The Justinian Code is still taught to law students on both sides of the Atlantic. The code was written by Tribonian, one of the emperor’s counselors who, as head of a commission of a dozen lawyers, created the imperial constitution in 533-534 AD. Art history, however, has been kinder to Justinian than Tribonian because the lawyer had far less illustrious portraits (one of them is actually in the U.S. House of Representatives) than his imperial master.

Emperor Justinian and his retinue (547 AD). Basilica San Vitale, Ravenna. Photo: Roger Culos via Wikimedia Commons

The most magnificent image of Justinian has been proudly displayed for almost 1500 years in Ravenna in eastern Italy. The Basilica San Vitale was built between 526-547 AD, amid the ongoing struggles between the Ostrogoth tribes and the Byzantine empire for the control of that land. The church was decorated with hundreds of thousands of mosaic tiles, all glittering with gold, polished stone, and brightly colored glass. The most famous and resplendent are the two panels portraying Justinian and his imperial consort Theodora surrounded by bishops and courtiers.

Copy of Paul Rubens’s The Judgement of Solomon (between 1617-1640). Prinsenhof Museum, Delft, The Netherlands. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

While artistic representations of Hammurabi and Justinian created during their lifetimes have survived until our times, this is not the case for Solomon, the King of Israel, who exists in art only through hundreds of years of artists imagining stories from his life. The tale that has traveled through the centuries as an example of Solomon’s wise ruling is the proverbial Solomonic judgement. As the Old Testament story goes, he was asked to decide which of two mothers should be given an infant that both women claimed belonged to them. When he slyly announced that the infant would be cut in half since neither woman would yield her rights, the real mother stayed the swordman’s hand, indicating she would rather give up her child than see it slain. That dramatic scene has been an extremely popular subject for some of the grandest names in art—Raphael, Giorgione, de Ribera, Blake, and Poussin. I chose the one above not only because it was glamorously painted by no less than Paul Rubens, but also because…it no longer exists. The original canvas, together with five other works by Rubens, burned in a fire in 1695 when the French army of King Louis XIV bombarded Brussels City Hall. Fortunately, some copies of The Judgement of Solomon from Rubens’ workshop survived. The illustration above is from the copy preserved in the Netherlands; another one that survived is in the Copenhagen State Art Museum. Nevertheless, the loss of the original is such a pity. Not all Rubensian historic compositions have such precise drawings and visual organization as this one. Here, the good mother and the just king are “color coded” in warm tones of gold and red, while the false mother and the henchman are contrasted with the dark purple and black. There is no room for emotional doubt here—the lines of justice are clearly marked.

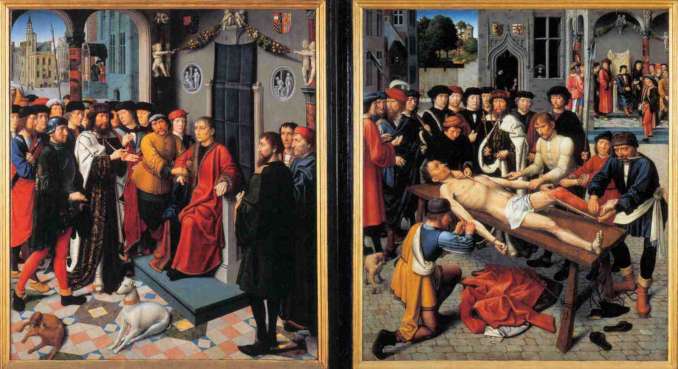

Gerard David. The Judgement of Cambyses (1498). Groeninge Museum, Bruges, Belgium. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

While the majority of historical paintings have tended to be based on either biblical scenes (like the Solomonic judgement) or real military events, The Judgement of Cambyses by Northern Renaissance artist Gerard David is based on The Histories by Greek scholar Herodotus. The painting tells the story of Persian king Cambyses, who ordered the arrest and flaying of a corrupt judge called Siamnes. Cambyses ruled in 6th-century BC, but Gerard David painted this work at the end of the 15th century, so this is an allegory rather than any attempt to illustrate Persian life during a long-gone empire. The left panel shows the corrupt judge’s arrest, while the right panel depicts a gruesome scene of tearing off the judge’s skin. This diptych was a commission from the city council for the town hall of Bruges (in today’s Belgium). The vivid if scary scene was designed to squash any idea of corruption among the city’s lawmakers. The huge panel of The Judgement of Cambyses is probably David’s most famous work, portraying not only all the details of the figures of the king (in white) and the judge (in red), but even a tiny detail of Siamnes’s crime of taking bribes (the two small figures in the doorway). Funnily enough, though this is a Flemish picture, the painter was much influenced by Raphael and other Italian artists, so he placed incongruously sweet cherubs and a fruit garland above the judge’s seat. You can see in this painting how the severe Northern Renaissance style is fighting with the much sweeter influence from Tuscany down south.

Henri-Frédéric Schopin. Divorce of Empress Joséphine from Napoleon on Dec. 15, 1809 (1843). The Wallace Collection, London. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

In all my years of visiting my favorite UK museum, the Wallace Collection, I have never noticed this mid-19th-century French painting that imagines the moment when Josephine was forced to divorce Napoleon in 1809 to make way for his ambition to sire a son and extend his dynasty. Divorce of Empress Joséphine from Napoleon on Dec. 15, 1809 was painted in 1843 by Henri-Frédéric Schopin. The painting is not particularly brilliant as art, which is probably one of the reasons it is not prominently displayed in a museum that has Poussin, Watteau, Fragonard, and Boucher on its walls, to mention just the French masters in the Wallace Collection.

The Schopin painting is noteworthy, though, for presenting a pivotal moment from the history of Napoleon’s reign. Josephine, assisted by Hortense, the Queen of Holland and her daughter from her first marriage, is about to sign an act of separation, while Napoleon looks on, somber and brooding. Incidentally, it was his infidelity and fathering of two sons (one with his mistress Eléonore Denuelle and another one with the Polish duchess Maria Walewska) that made Napoleon realize that he was not infertile, but simply unable to father an heir with his current wife. The separation was more or less consensual for dynastic reasons—these were grounds for divorce that Josephine accepted and the new civil code allowed.

Even if this canvas is not the most accomplished, it is a perfect illustration of how Napoleon applied to his own life the Code that he had introduced to the French judicial system in 1804. The Napoleonic Code unified numerous previous laws into one system that managed property, personal life, and the power of the state—a legal framework that is still in use in France and is the basis of systems in places that Napoleon’s army ruled, such as Italy, Spain, and the Netherlands. The emperor was keenly aware that introducing the reformed and codified laws would make him much more immortal than his military career. In 1815 during his imprisonment on the island of Elba, he presciently declared: “My real glory is not the 40 battles I won—for my defeat at Waterloo will destroy the memory of those victories. . . . What nothing will destroy, what will live forever, is my Civil Code.”

Merry-Joseph Blondel. Napoleon visiting the Tribunat (1807). Palais- Royal, Paris. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Napoleon’s contemporary British biographer Andrew Roberts praised the emperor’s influence on European justice systems with these wise words:

“The ideas that underpin our modern world—meritocracy, equality before the law, property rights, religious toleration, modern secular education, sound finances, and so on—were championed, consolidated, codified and geographically extended by Napoleon. To them he added a rational and efficient local administration, an end to rural banditry, the encouragement of science and the arts, the abolition of feudalism and the greatest codification of laws since the fall of the Roman Empire.”

William Hogarth. An Election Entertainment (ca. 1755). Sir John Soane Museum, London. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Speaking of Britain—one of the first modern countries to regulate society’s life with a parliamentary system of power—here is a satirical painting by British artist William Hogarth. An Election Entertainment, one of a four-painting series that was subsequently turned into Hogarth’s famous engravings, is a colorful panorama of political vices associated with 18th-century elections. In the mid-18th century, the English parliamentary system was quite a new invention, full of imperfections. Hogarth shows the election candidates on the left—in order to get votes, they must endure the unwanted kisses of unattractive housewives, disregard a ring being stolen from their finger, and provide bribes as displayed in the picture’s front left. The other characters in the picture are those who would not have had the right to stand for parliament or even vote directly (since only about 16,000 men who owned land could vote), but who would be courted to buy the services of the men elected. Hogarth mercilessly shows all the manifestations of corruption and excess that accompanied elections at the time. He even provides some helpful captions that comment on marriage and anti-Semitic laws, as well as expressing criticism of the Hanoverian dynasty. Even if most of these clues are meaningless to us now, Hogarth’s idea of political criticism through art continues to flourish in our times. These days, they may take on the form of a political cartoon or Banksy’s graffiti, but they still use the visual arts for social and legal commentaries.

Banksy. Bethlehem (2005). Photo: Markus Orkner/Wikimedia Commons